It was almost shameful that President Trump on January 12th signed a proclamation honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In all honesty, I cringe at his signing of this proclamation. I cringe because the president honors Dr. King while dishonoring Dr. King’s legacy.

It was almost shameful that President Trump on January 12th signed a proclamation honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In all honesty, I cringe at his signing of this proclamation. I cringe because the president honors Dr. King while dishonoring Dr. King’s legacy.

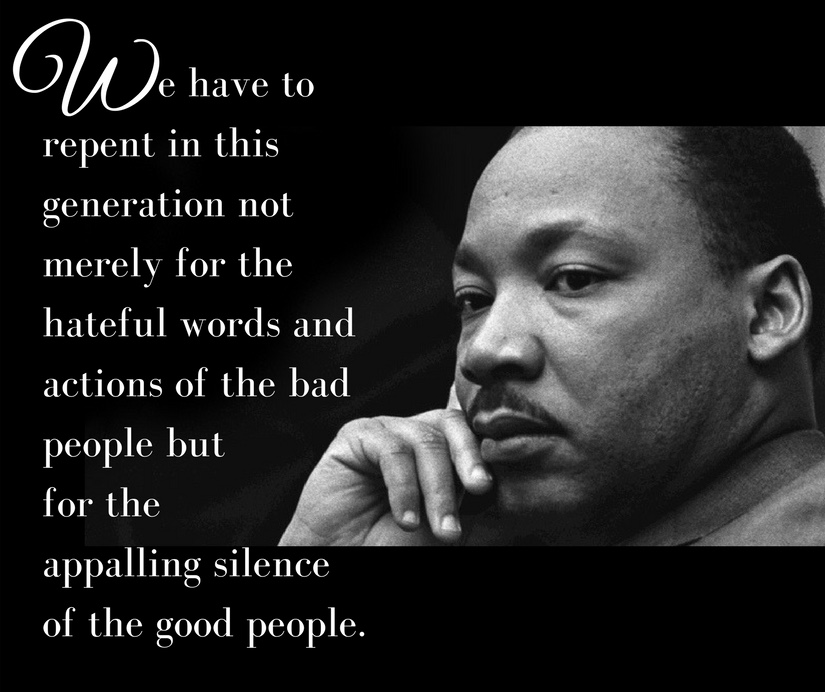

I can imagine that Dr. King’s words echoed through the Oval Office during the signing, in a whisper heard only by persons of love and good will.

If we are to have peace on earth, our loyalties must become ecumenical rather than sectional. Our loyalties must transcend our race, our tribe, our class, and our nation; and this means we must develop a world perspective.”

We’ve learned to fly the air like birds, we’ve learned to swim the seas like fish, and yet we haven’t learned to walk the Earth as brothers and sisters…”

― Martin Luther King, Jr.

I cringe because I heard the words that the president said about “shithole countries.”

Why do we want all these people from Africa here? They’re shithole countries … We should have more people from Norway.

– Donald J. Trump

In his remarks, Mr. Trump, who has vowed to clamp down on illegal immigration, also questioned the need for Haitians in the United States.

Instantly, many Democrats and some Republican lawmakers called out the president. Republican United States Representative Mia Love, a daughter of Haitian immigrants, said the comments were “unkind, divisive, elitist, and fly in the face of our nation’s values,” and she called forTrump to apologize to the American people and to the countries he denigrated.

Another Republican Representative, Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, who was born in Cuba and whose south Florida district includes many Haitian immigrants, said: “Language like that shouldn’t be heard in locker rooms and it shouldn’t be heard in the White House.”

Democratic Senator Richard Blumenthal said the president’s comment “smacks of blatant racism, the most odious and insidious racism masquerading poorly as immigration policy.”

A wave of international outrage also grew against the president’s vulgar language as the president of Ghana, President Nana Akufo-Addo, said that he would “not accept such insults, even from a leader of a friendly country, no matter how powerful.”

The Ghanian president tweeted an unflinching defense of the African continent — and of Haiti and El Salvador, countries that Trump also mentioned in the Thursday meeting with a group of senators at the White House.

In addition to Ghana, the government of Botswana said Trump’s language is “reprehensible and racist,” and said it has summoned the U.S. ambassador to clarify what he meant.

Senegal’s president, Macky Sall, said in a statement that it was “shocking” and that “Africa and the black race merit the respect and consideration of all.” His West African nation has long been praised by the United States as an example of a stable democracy.

The African Union, which is made up of 55 member states, also spoke against Trump’s remarks.”Given the historical reality of how many Africans arrived in the United States as slaves, this statement flies in the face of all accepted behavior and practice,” said spokeswoman Ebba Kalondo.

Paul Altidor, Haiti’s ambassador to the U.S., called Trump’s comments “regrettable” and based on “clichés and stereotypes rather than actual fact.” He also noted the insensitivity of its timing, coming the same week as the eighth anniversary of Haiti’s 2010 earthquake, which killed more than 200,000 people.

El Salvador’s government on Friday sent a formal letter of protest to the United States over the “harsh terms detrimental to the dignity of El Salvador and other countries.”

A spokesperson representing the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights condemned President Trump’s “shocking and shameful” comment, saying: “I’m sorry, but there’s no other word one can use but racist.”

On January 13th, The Washington Post published an article by Karen Tumulty that calls out President Trump’s misunderstanding of this nation’s immigration history.

There is far more to the latest controversy surrounding President Trump than the vulgar and implicitly racist language he used to draw a distinction between desirable and undesirable immigrants. Trump’s choice of words also revealed a deeper and more substantive truth about how the president views — and misunderstands — America’s unique relationship with its immigrants.

Trump’s words, with their racial connotations, also suggest he wants to return to what has come to be regarded as one of the more shameful and xenophobic periods of immigration policy.

In 1924, a set of laws was passed that set quotas limiting the number of people admitted to this country based on where they came from, with a goal of preserving the United States’ ethnic homogeneity.

“The premise of national origin quotas was that some countries produce good immigrants, others produce bad immigrants,” said NPR correspondent Tom Gjelten, author of the 2015 book “A Nation of Nations: A Great American Immigration Story.”

“There were actually ‘scientific’ studies purporting to categorize countries according to the quality and characteristics of their people, and the quotas were devised in part on the basis of the testimony of ‘expert’ opinion,” Gjelten said.

There are so many voices of reason, voices that cry out for dignity, respect, unity and love, speaking out against the president of the United States. So it is with sadness and shame that I celebrate the day of remembrance for Dr. King. On his day in 2018, I hear more intensely all that he taught us about so many things, and I hear what he shared with us most profoundly — the power of love.

Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.

Hate multiplies hate, violence multiplies violence, and toughness multiplies toughness in a descending spiral of destruction. So when Jesus says “Love your enemies,” he is setting forth a profound and ultimately inescapable admonition.

― Martin Luther King, Jr., from Strength to Love

This week, I heard a provocative statement: that hate speech is not about who Donald Trump is. Rather, it is about who we are. The statement opened up some questions for me:

How do I respond? What does it mean for me to stand with those who are marginalized?

Is it not my responsibility to stand up to persons in seats of power when they promote hate, racism, xenophobia, exclusion and hostility?”

Will I set my face towards love and my heart towards the world as it is seen through the eyes of Jesus? Is it not up to me to be a part of creating — in our nation and in our world — a “beloved community?”

For “hate cannot drive out hate. Only love can do that.” Was

On this day — the day we usually spend celebrating America each year — some of us are lamenting because we don’t feel much like celebrating. The children and families separated at our borders leave us feeling deep-down-where-it-hurts grief. And it is not that we look at the border fiasco as the crisis “du jour.” No. The toddlers in detention centers have come on the heels of the Parkland shooting and the protests it sparked around the nation and throughout the world when all of us cried out in unified voice, “Not our children,”

On this day — the day we usually spend celebrating America each year — some of us are lamenting because we don’t feel much like celebrating. The children and families separated at our borders leave us feeling deep-down-where-it-hurts grief. And it is not that we look at the border fiasco as the crisis “du jour.” No. The toddlers in detention centers have come on the heels of the Parkland shooting and the protests it sparked around the nation and throughout the world when all of us cried out in unified voice, “Not our children,” June 16, 2012 . . . My three-year-old granddaughter standing among the bronze sculptures of The Little Rock Nine.

June 16, 2012 . . . My three-year-old granddaughter standing among the bronze sculptures of The Little Rock Nine. And my granddaughter stands in front of Little Rock Central High, a school she may choose to attend someday, a school she will be able to attend because The Little Rock Nine took a dangerous risk to make it possible.

And my granddaughter stands in front of Little Rock Central High, a school she may choose to attend someday, a school she will be able to attend because The Little Rock Nine took a dangerous risk to make it possible. Finally, my granddaughter stands playfully on the steps of the Arkansas State Capitol. I know that it is possible that she may one day proudly walk through its golden doors as a state senator or representative. That is possible because nine Little Rock students were brave enough to be a part of changing history.

Finally, my granddaughter stands playfully on the steps of the Arkansas State Capitol. I know that it is possible that she may one day proudly walk through its golden doors as a state senator or representative. That is possible because nine Little Rock students were brave enough to be a part of changing history. Because of the recent opening of The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, I have been contemplating the terror of lynching in our history. The Montgomery site is the nation’s first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with police violence.

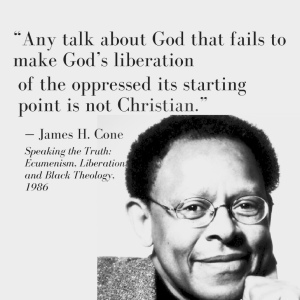

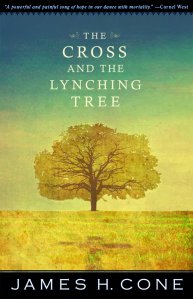

Because of the recent opening of The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, I have been contemplating the terror of lynching in our history. The Montgomery site is the nation’s first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with police violence. While in seminary, I immersed myself in the study of liberation theologies. Not surprisingly, my research led me to the writings of black liberation theologian, The Rev. Dr. James H. Cone. I became what some might call a follower of Dr. Cone. I saw him as a Christ-like superhero. Much of my research and writing in those days delved into the history of liberation theology, so Dr. Cone’s books covered my desk for months.

While in seminary, I immersed myself in the study of liberation theologies. Not surprisingly, my research led me to the writings of black liberation theologian, The Rev. Dr. James H. Cone. I became what some might call a follower of Dr. Cone. I saw him as a Christ-like superhero. Much of my research and writing in those days delved into the history of liberation theology, so Dr. Cone’s books covered my desk for months. Google it.

Google it.

I invite you to read “Out of Africa: White supremacy and the Church’s silence,” a provocative opinion piece by our guest blogger, Dr. Bill J. Leonard. Many thanks to Dr. Leonard for prompting us to more fully commemorate the day honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. If you are willing to challenge yourself, these words will shed the light you need to do so.

I invite you to read “Out of Africa: White supremacy and the Church’s silence,” a provocative opinion piece by our guest blogger, Dr. Bill J. Leonard. Many thanks to Dr. Leonard for prompting us to more fully commemorate the day honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. If you are willing to challenge yourself, these words will shed the light you need to do so.

It was almost shameful that President Trump on January 12th signed a proclamation honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In all honesty, I cringe at his signing of this proclamation. I cringe because the president honors Dr. King while dishonoring Dr. King’s legacy.

It was almost shameful that President Trump on January 12th signed a proclamation honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. In all honesty, I cringe at his signing of this proclamation. I cringe because the president honors Dr. King while dishonoring Dr. King’s legacy.